- Do + See

- Dine + Host

- Give + Join

- Educate + Learn

Merry Celebrations | Tying the Knot at the Taft

By Angela Fuller, Assistant Registrar/Curatorial Assistant

December 24, 1807: Nicholas and Susan Longworth

“If ever there was time for joy—

For man and woman, girl and boy

To dance and sing, to shout and laugh,

The toast to pledge, the cup to quaff,

Of bright Catawba, sparkles shedding,

‘Tis on this gladsome GOLDEN WEDDING!”

These festive lines are found in an illustrated book commemorating the “Golden Wedding”—meaning the fiftieth wedding anniversary—of former Taft historic house residents Nicholas Longworth and Susan Howell Connor Longworth. The couple had lived in the Pike Street mansion for nearly thirty years by the time this merry event occurred. In the book, poems humorously recount short biographies of the bride and groom, how they met, and their nuptials on Christmas Eve in 1807, among other events. According to this account, the Longworths were married in a double ceremony, with both brides named Susan. Nicholas, a young lawyer at the time, apparently worked so late on his own wedding day that he barely had time to shave or dress properly. Despite this inauspicious beginning:

“. . . they would, for fifty years,

Of clouds and sunshine, smiles and tears,

Exist together ‘neath the sun

In loving union joined as one—"

Title page, from Memorial of the Golden Wedding of Nicholas and Susan Longworth Celebrated at Cincinnati on Christmas Eve, 1857, color lithograph, Hunckel & Son, Baltimore. Taft Museum of Art

The Golden Wedding book’s title page presents an abbreviated version of the Longworths’ love story. At top left, the young Nicholas and Susan clasp hands as Cupid emerges from a rose, preparing to shoot them with an arrow. Below these figures, cherubs frolic among grapevines, bearing symbols of the couple’s longevity and prosperity: an evergreen tree, a cornucopia of flowers, and a bottle of Longworth’s famous sparkling Catawba wine. An anchor at the bottom left corner of the page, near another portrait of the lovers, signifies their steadfast bond. In this second depiction, an older Nicholas and Susan seem to merge into one entity, their heads appearing to sprout from the same body. On another page, detailed likenesses of the two remain separate but firmly entwined within the same elaborate frame. These sentimental words and images of the couple may seem somewhat saccharine to us today, but they reflect a new attitude toward family life that arose in 19th-century America: the concept that mutual affection and personal compatibility—rather than the acquisition of wealth, status, or resources—could be an ideal foundation for marriage.

Eliza Potter, a hairdresser hired to style Susan Longworth’s hair for the party, describes the celebration:

“Never again, do I expect to witness in this city, or perhaps anywhere, such a scene as I saw that night. There was an immense number assembled; old and young and middle aged and all, seemed full of happiness. Tables were set in two large rooms that opened into each other; they were elegantly and beautifully spread, filled with every delicacy, and all kinds of wine.” (Eliza Potter, A Hairdresser’s Experience in High Life, published by the author, Cincinnati: 1859, reprinted by the University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill: 2009.)

December 4, 1873: Charles and Anna Taft

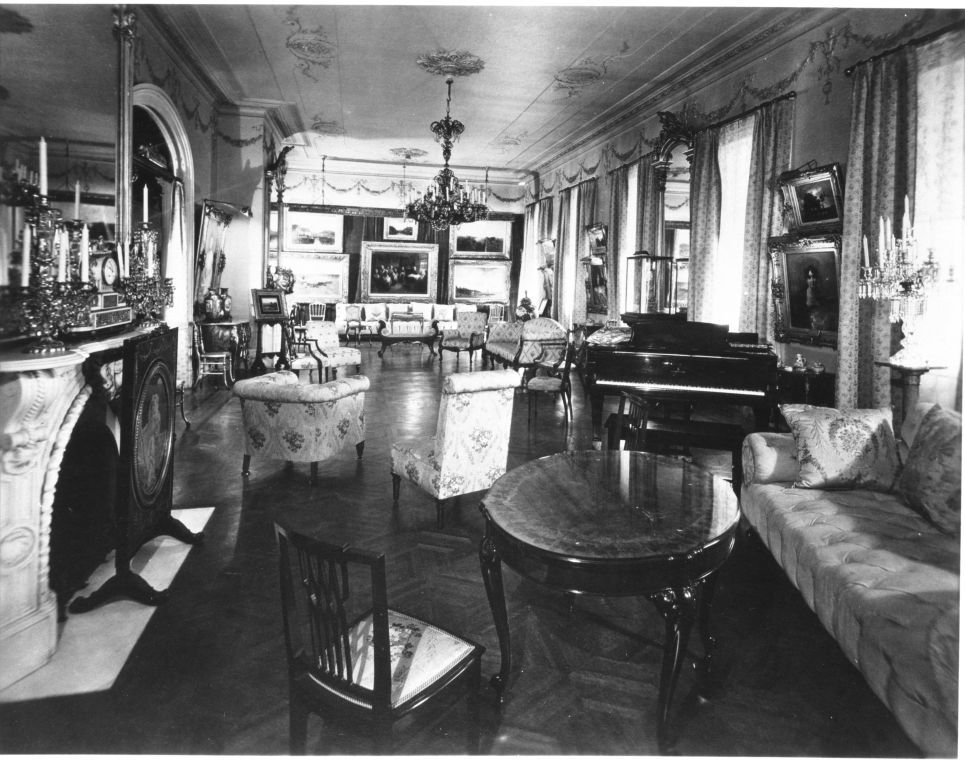

This photograph of the Music Room was taken around 1925, not long after the Tafts too would have celebrated their fiftieth wedding anniversary.

Like the Longworths, Anna Sinton Taft and Charles Phelps Taft, the Pike Street residence’s final occupants, also celebrated their wedding anniversary in December. The Tafts were married in the house’s “large main salon” (now called the Music Room) on December 4, 1873.

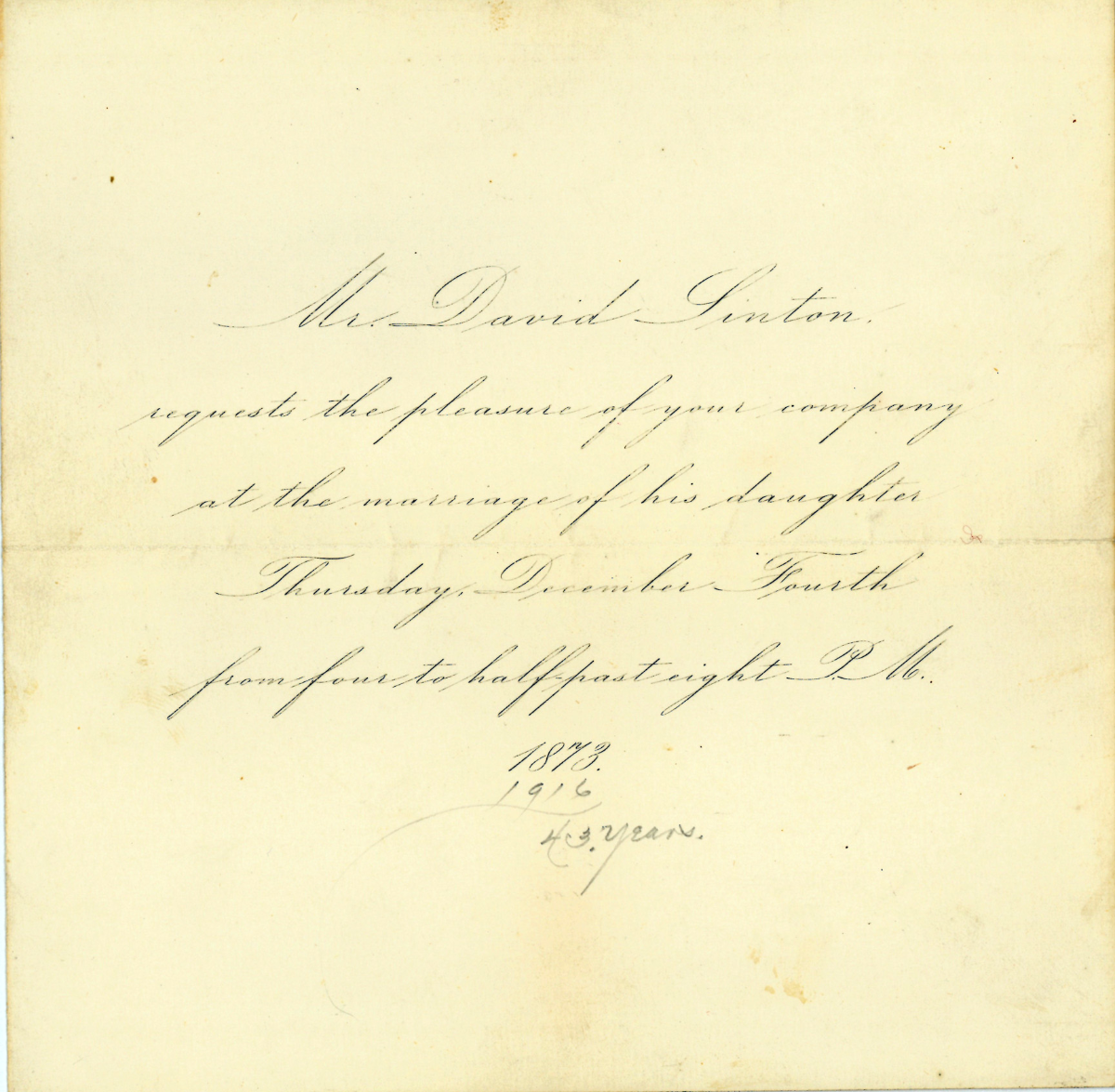

As Anna was the only surviving child of multimillionaire David Sinton and his late wife Jane Ellison Sinton, no expenses were spared for this joyous occasion. The Cincinnati Enquirer proclaimed the Sinton-Taft wedding the “social event of the season” and printed a lavish description of it the following day:

“The nuptials . . . were . . . surrounded by all that glamour which flowers, the garnering of which depletes hot-houses, and music that fills the air with sensuous melody, can envelop the union of man and woman in marriage, the consummation of youthful love. . . . The bridal party stood under an exquisite canopy of evergreens, just opposite the main door of the parlor. . . . From the center of the ceiling . . . hung a marriage-bell of pure white exotics of exquisite beauty. . . . The bride’s dress was of . . . satin, cut low and demi-trained, trimmed heavily with [lace], and gracefully trimmed with orange flowers. . . . The ornaments were pearls and diamonds.” (“Nuptials Extraordinary: The Taft-Sinton Wedding Last Night—The Social Event of the Season,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 5, 1873)

Invitation to the wedding of Charles Phelps Taft and Anna Sinton, December 4, 1873, Taft Museum of Art Archives

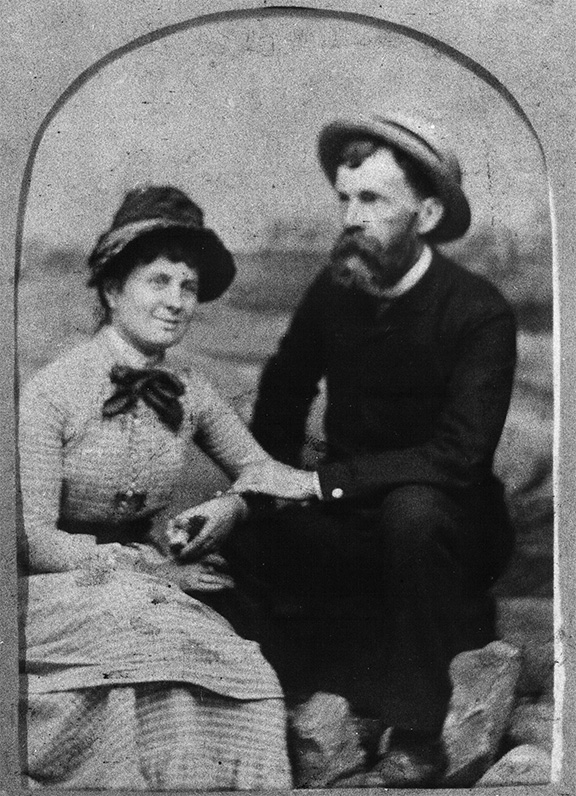

Charles Phelps Taft and Anna Sinton Taft, about 1880; original photograph in the collection of the William Howard Taft National Historic Site (United States National Park Service)

This photograph of the happy couple was taken about seven years into their marriage, when the Tafts were in their thirties, the parents of three small children. Anna casually rests her arm on Charles’s knee, and their limbs form a visual knot at the center of the image, a gesture that appears genuinely affectionate. The Tafts lived to enjoy more than fifty years of marriage in their mansion, where together they built a family, an art collection, and founded a museum.

The next time you visit the Taft Museum of Art, consider the countless happy times that have taken place inside it—200 years of anniversaries, birthdays, holiday celebrations, family reunions, parties, and weddings. This history makes the Taft such a special place.