- Do + See

- Dine + Host

- Give + Join

- Educate + Learn

The Strike Is On! The Boot & Shoe Workers’ Union

By Ann Glasscock, Assistant Curator

Amalgamated Lithographers of America, Pocket Mirror, about 1910, Newark, New Jersey, celluloid and mirror glass, New-York Historical Society

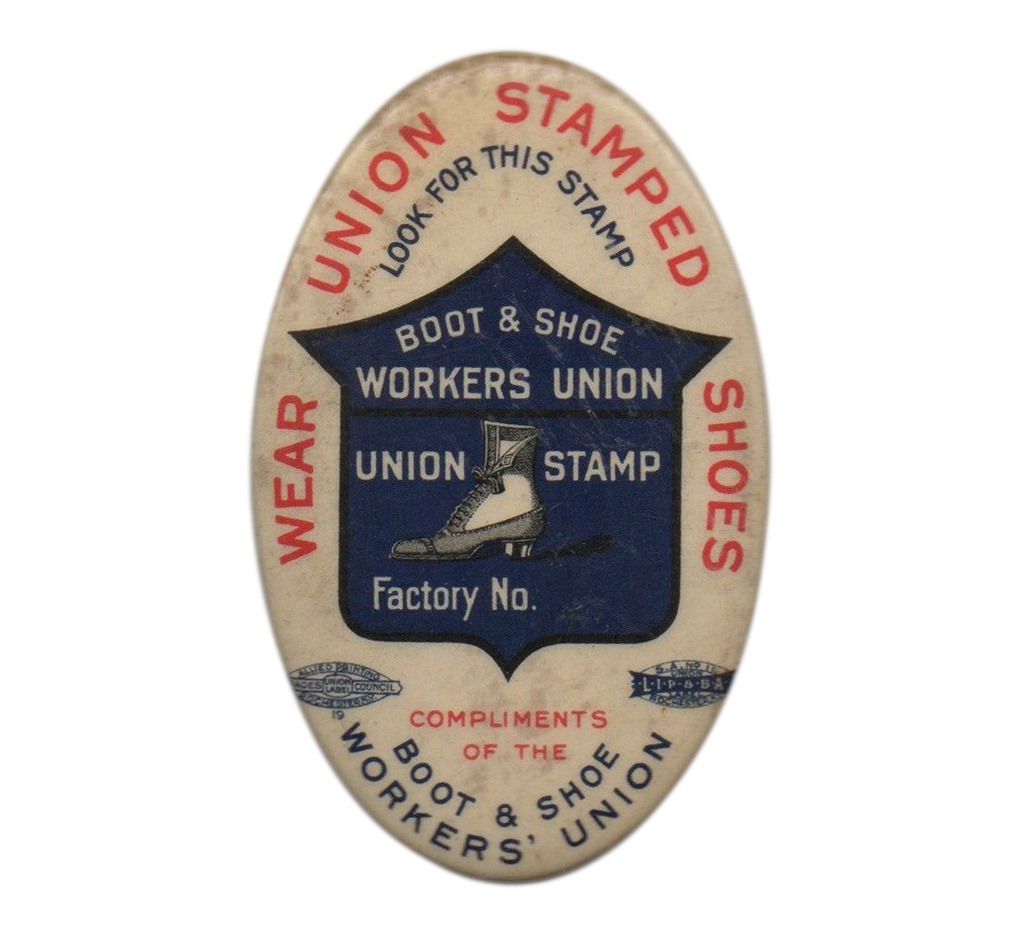

“Wear Union Stamped Shoes” declared the Boot & Shoe Workers’ Union, whose slogan you can see on this pocket mirror in the Taft Museum of Art's latest special exhibition, Walk This Way | Footwear from the Stuart Weitzman Collection of Historic Shoes. This mirror, along with a shoe from the early 1900s, sparked the inspiration for my latest Museum Musings.

Made from leather and with tear-drop-shaped cutouts on the instep, this eye-catching shoe was made around 1915. A woman probably wore something like this when she went dancing—the intricate beadwork, which resembles stylized leaves and flower blossoms, perhaps twinkling in just the right light. So, you might be wondering what’s so special about it? What makes it relevant to a blog about union activism?

On the bottom of this shoe is the stamp of the Boot & Shoe Workers’ Union. Considered radical for its time, the union’s 1904 constitution called for fair “wages and conditions of employment”; the elimination of child labor; and “uniform wages for the same class of work, regardless of sex.” This stamp tells us that the people who made this shoe fought for job quality and job equality. It also shows off the high standard of craftsmanship valued by American shoemakers.

In the early 20th century, unions were active across the United States. According to the Shoe Workers’ Journal:

"Cincinnati is one of the most peaceful shoe towns. All prices and conditions of work are negotiated between the local unions of the Boot and Shoe Workers’ Union and the Manufacturers’ Association every year. Each succeeding year sees a betterment of the wages and working conditions of the shoe workers. There is no other large shoe manufacturing community where the union stamp and arbitration contract does not prevail that approaches Cincinnati in its condition of tranquility, or peaceful adjustment of controversies over shoe labor."1

Little did the author of this 1919 editorial know that just three years later, thousands of Cincinnati shoe workers would be walking off the factory floor.

Buttoned Shoe, about 1915, leather, beads, and buttons, Stuart Weitzman Collection, no. 25. Photo credit: Glenn Castellano, New-York Historical Society

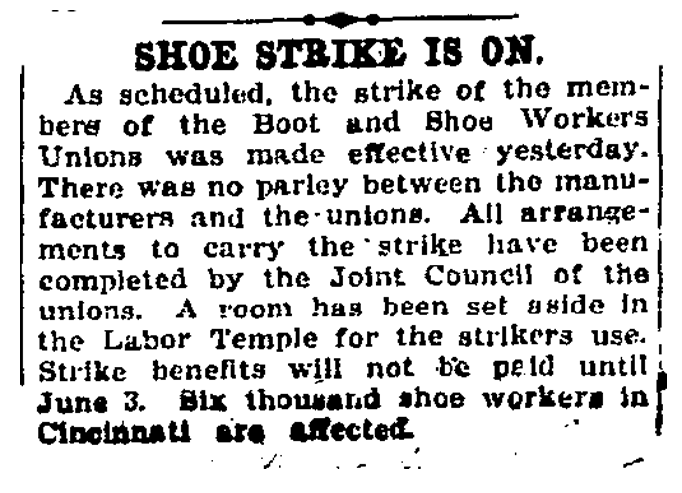

“Shoe Strike Is On,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 21, 1922, 31.

“Shoe Strike Is On” declared the Cincinnati Enquirer!2 On May 20, 1922, members of the Boot & Shoe Workers’ Union walked out after manufacturers and workers refused to come to an agreement about a proposed reduction in wages. Male workers were asked to take a 25 percent cut; women in fitting departments (where shoes were stitched), 15 percent; and women in packing departments, 10 percent. Workers countered with a 10 percent wage reduction across the board, but manufacturers refused.3 Strikers rallied at Cincinnati’s Workman’s Hall, aka the “Labor Temple,” which served as headquarters for a number of labor organizations, including the Boot & Shoe Workers’ Union.

After ten weeks, workers were still on strike. On July 26, representatives of the Cincinnati Boot and Shoe Manufacturers’ Association and the Cincinnati Boot & Shoe Workers’ Union met to try and settle their differences. Unfortunately, neither side was willing to budge, and a deadlock ensued. Luckily, workers continued to be paid full benefits.

Finally, in December, the strike ended. Members of the strike committee and the manufacturers association had come to an agreement. The new terms called for a 5 percent reduction on “piecework and day hands . . . and it is understood that the reduction will not apply to any day work operatives earning less than $14.00 per week.” The Shoe Workers’ Journal reported that the Cincinnati strike was significant:

"It was large in that over 3,000 members laid down their tools. It was long in that it lasted nearly seven months. It was noteworthy that in all that time less than 100 members deserted the cause. It proved that where workers are united they are invincible. The Cincinnati members maintained a united front and refused to divide under any circumstances."4

Cincinnati’s shoe workers—who went on strike nearly one hundred years ago—were determined. What about you? What are you passionate about? What can you do to help bring about change?

Workman’s Hall, Over the Rhine, Cincinnati, postcard, early 1900s. Nelson and Florence Hoffmann Cincinnati Postcard Collection, Courtesy Archives & Rare Books Library, University of Cincinnati

1 The Shoe Workers' Journal 20, no. 4 (April 1919): 15.

2 “Shoe Strike Is On,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 21, 1922, 31.

3 An article in the Enquirer noted that the last “general” shoe strike in Cincinnati was in 1888, with a partial strike in 1911 (“Walkout of Shoeworkers Is Set,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 17, 1922, 20).

4 The Shoe Workers' Journal 24, no. 1 (January 1923): 12.