- Do + See

- Dine + Host

- Give + Join

- Educate + Learn

Guanyin: Bodhisattva, Goddess, Queer Icon

By Angela Fuller, Assistant Curator

Wandering through the Taft Museum of Art’s collection galleries, you might spy a miniature ceramic woman balancing in her bare feet on a huge flower. Her serene expression belies vast power. She represents Guanyin, a deity who transformed from male to female and gained a new name over two thousand years of being venerated.

Guanyin’s fascinating history begins in ancient India. This figure originated as the Buddhist bodhisattva of compassion, named Avalokiteśvara. Buddhists believe that existence is inextricably linked to pain and seek release from the cycle of life, death, and rebirth into a blissful state of peace called nirvana. Bodhisattvas are beings who selflessly delay their own nirvana to help free others from suffering. Ancient Buddhists called upon Avalokiteśvara by name for help with specific troubles: fire, drowning, attack by bandits, and infertility, among others.

Guanyin, Bodhisattva of Compassion, about 1796–1820, China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Jiaqing reign (1796–1820), enamel and gold on porcelain, 33 x 9 3/4 x 8 7/16 in. (83.82 x 24.77 x 21.43 cm). Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, Ohio. Bequest of Charles Phelps Taft and Anna Sinton Taft, 1931.168

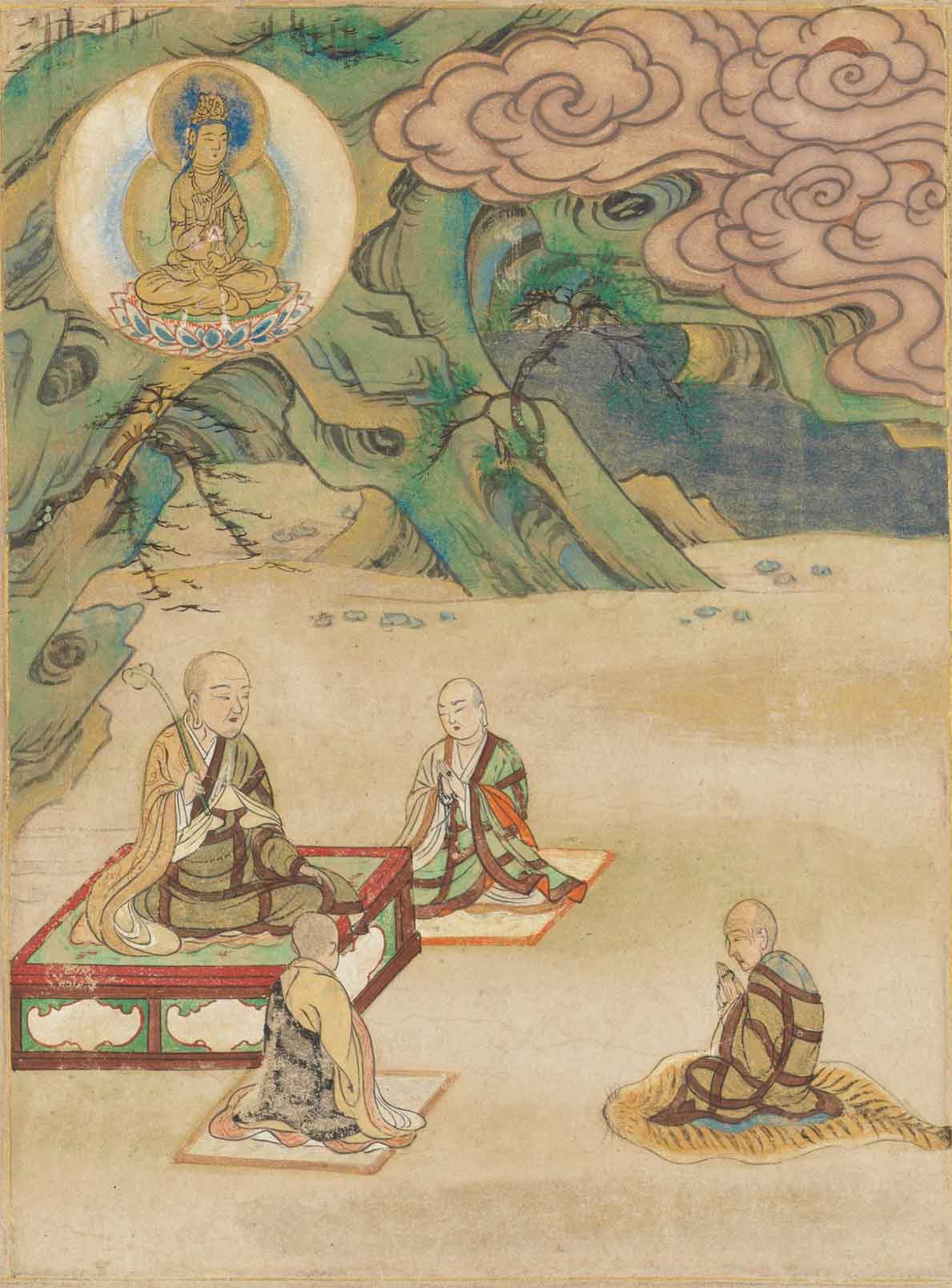

An early Buddhist text, the Lotus Sutra, describes Avalokiteśvara’s ability to shapeshift. Depending on the age, gender, profession, and social status of the individual who calls for help, the bodhisattva may appear in a variety of physical forms, even non-human ones. For example, in this medieval Japanese copy of the Lotus Sutra, Avalokiteśvara appears twice in each scene, once enclosed in a circle at top and again below, in a form corresponding to those who need help: as seen below, left to right, gods, children, and monks. This signifies Avalokiteśvara’s nonjudgmental nature—every living being is worthy of the bodhisattva’s help finding safety and peace.

Sugawara Mitsushige (Japanese, active mid-1200s), “Universal Gateway,” Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra (detail images), 1257, Kamakura period (1185–1333), Japan, handscroll; ink, color, and gold on paper, 9 11/16 in. x 30 ft. 8 1/16 in. (24.6 x 934.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Purchase, Louisa Eldridge McBurney Gift, 1953, 53.7.3

Sugawara Mitsushige (Japanese, active mid-1200s), “Universal Gateway,” Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra (detail images), 1257, Kamakura period (1185–1333), Japan, handscroll; ink, color, and gold on paper, 9 11/16 in. x 30 ft. 8 1/16 in. (24.6 x 934.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Purchase, Louisa Eldridge McBurney Gift, 1953, 53.7.3

Sugawara Mitsushige (Japanese, active mid-1200s), “Universal Gateway,” Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra (detail images), 1257, Kamakura period (1185–1333), Japan, handscroll; ink, color, and gold on paper, 9 11/16 in. x 30 ft. 8 1/16 in. (24.6 x 934.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Purchase, Louisa Eldridge McBurney Gift, 1953, 53.7.3

Buddhists also believe that bodhisattvas, as enlightened beings, transcend earthly limitations—such as the need to occupy a physical body—and are therefore neither male nor female. Despite Avalokiteśvara’s elastic gender, Indian artists generally portrayed this bodhisattva as a young man.

The Lotus Sutra arrived in China in the first few centuries CE. The Sanskrit name Avalokiteśvara translated to Guanyin in Chinese. Both names roughly mean “one who hears the world’s cries.” For several hundred years, Chinese artists continued to depict Guanyin in masculine form.

Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva of Compassion, about 475–500, Sarnath, Uttar Pradesh, India, Gupta Dynasty (about 300–about 550), sandstone, 48 1/2 x 15 1/2 x 7 inches (123.2 x 39.4 x 17.8 cm), weight: 290.5 lb. (131.77 kg). Philadelphia Museum of Art. Stella Kramrisch Collection, 1994-148-1

Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin), 1282, China, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), wood with traces of pigment, 39 1/4 in. (99.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1934, 34.15.1a, b

However, during the early Song dynasty (960–1279), Guanyin began appearing more frequently as a woman in art, even as Buddhist artists elsewhere in Asia continued to picture the bodhisattva as a man. Chinese Buddhists also developed their own legends surrounding Guanyin. In one, Guanyin inhabits the body of a mortal woman, Princess Miao Shan. Eventually, Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike in China came to worship the feminine Guanyin as a goddess.

Medieval Chinese women, faced with pressure to produce a male heir and continue the family name, popularized Guanyin as a giver of sons. A pair of ceramic Guanyin figures on view in the Taft Museum of Art’s Gallery 7: Portraits & Prosperity, showcase this version of the deity. Each holds an infant in her lap, ready to relinquish him to a couple desiring a child.

Guanyin’s gender fluidity resonates today with some members of the LGBTQ community, particularly transgender and nonbinary individuals—an uncommon opportunity for those who seldom see themselves reflected in art history. Moreover, queerness is not pictured as a negative characteristic, but is embodied in a benevolent and powerful goddess. Equally significant are Guanyin’s infinite compassion and willingness to engage all living beings on their own terms, cementing the bodhisattva’s latest transformation into a modern queer icon.

Guanyin, Bodhisattva of Compassion, about 1700, China, Qing dynasty (1644–1911), Kangxi reign (1662–1722), enamel on porcelain, 14 1/2 x 6 1/4 x 4 5/16 in. (36.83 x 15.88 x 10.95 cm); 14 5/8 x 6 1/4 x 4 1/4 in. (37.15 x 15.88 x 10.8 cm). Taft Museum of Art, Cincinnati, Ohio. Bequest of Charles Phelps Taft and Anna Sinton Taft, 1931.44, 49

About the author

Angela Fuller, Assistant Curator

As the Taft Museum of Art’s assistant curator, Angela Fuller is involved in planning the museum’s temporary exhibitions as well as research and interpretation of the permanent collection. She has curated several exhibitions at the Taft, most recently Built to Last: The Taft Historic House at 200. Angela earned a BA in art history and a BFA in studio art at the University of Louisville in 2011, then completed a master’s degree in art history and museum studies at Case Western Reserve University in 2013. She interned at the Cincinnati Art Museum and the Cleveland Museum of Art before joining the Taft in 2016. Angela lives in Northern Kentucky with her two kiddos and miniature dachshund.