- Do + See

- Dine + Host

- Give + Join

- Educate + Learn

The Time is Ripe: Learning the Art of Watchmaking

by Ann Glasscock, Associate Curator

Have you ever wondered how the watches in the Taft Museum of Art’s collection were made? To better understand how watchmakers created the movements (i.e. the moving parts of a watch) housed in these small technological wonders, I took an introduction to watchmaking class at the American Watchmakers and Clockmakers Institute (AWCI). Located in Harrison, Ohio, just 30 minutes from downtown Cincinnati, the AWCI teaches a variety of courses for professionals as well as for beginners. In addition to classrooms, the institute houses the Henry B. Fried Resource Library and the Orville R. Hagans History of Time Museum. The AWCI also operates a state-of-the-art mobile classroom that travels throughout the country, bringing the art of watchmaking to a wider audience.

Wadsworth Watch Case (detail), Tiny Treasures Gallery, Taft Museum of Art

The American Watchmakers and Clockmakers Institute, with the and Archie Perkins Mobile Horology Classroom parked outside

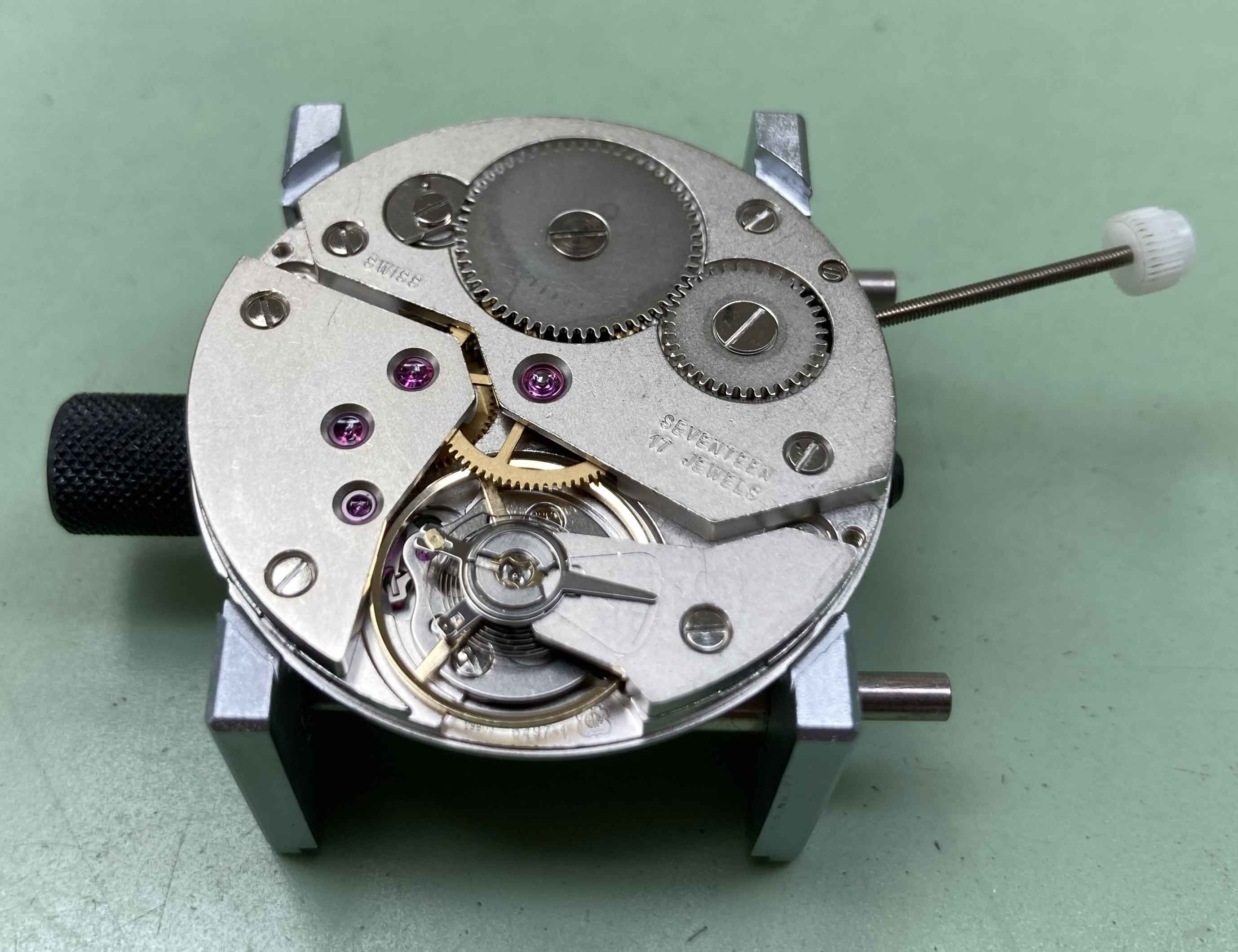

During my weeklong foundation course, I disassembled and reassembled a mechanical, or manual-wind, Swiss movement, specifically the ETA 6497-1. Its design is based on an 18th-century watch by Jean-Antoine Lépine, a French watchmaker. Often referred to as a “pocket watch movement,” these timepieces are quite large, making them the perfect training device for amateur watchmakers. The class was led by Alena Diaz, a female watchmaker based in Seattle, as well as AWCI Education Director Jason Champion and watchmaker Christopher Wheeler. Of the eleven students in attendance, three were women, which is noteworthy given that watchmaking has traditionally been a male-dominated field.

ETA 6497-1, front, before disassembly

ETA 6497-1, back, before disassembly

Alena Diaz, course instructor

To get started, we donned our loupes—optical tools used to magnify objects—and began disassembling the movement. We placed each of the nearly 40 parts in two metal baskets that later went into a cleaning machine. Dust, lint, and other fibers can negatively affect the way a watch functions, so remember, a clean watch is a happy watch! After a thorough cleaning, we began putting the movement back together, lubricating various parts along the way in addition to the jewels—the tiny purplish-red discs seen in the photo nearby. Jewels, now made from synthetic rubies, help reduce friction and keep watches running smoothly.

Ann Glasscock examining the movement

Watch cleaning baskets

View of the movement, including several jewels

After reinstalling the dial and hands, it was then time to calibrate the watch to ensure it would perform accurately. First, we demagnetized the movement. Next, we used a timing machine to calculate rate, amplitude, and beat error. A series of formulas helped us to further crunch the numbers. Once everything checked out, we placed the watch crystal and bezel back on the dial, casing the movement back up, and voila! Listening to its gentle ticking sound and seeing it keep time was extremely gratifying.

Having learned how complex a basic modern movement could be gave me newfound respect for the 17th- and 18th-century watchmakers who made the Taft’s timepieces. These highly skilled individuals explored new horological technologies, and they excelled at fine craftsmanship. They made watch parts—every wheel, every screw—sometimes with the aid of machinery like a lathe, sometimes by hand using small saws, files, and drills. (And let’s not forget about the goldsmiths and enamel artists who made the cases!)

Astronomical Watch with a Calendar (detail), about 1650–75, probably Geneva, Switzerland, silver and gilded brass. Taft Museum of Art, 1932.52

Impressed yet? Next time you’re at the Taft, check out our spectacular collection of watches. Museum founders Charles and Anna Taft acquired these timepieces through a single purchase from a Paris-based art dealer in 1905. My favorite is Watch with the Judgment of Paris, the interior of which displays a variety of finely painted flowers. What’s yours?

Caspar Cameel (French, active from about 1625), watchmaker, Watch with the Judgment of Paris, about 1640, with early- to mid-17th-century movement (Strasbourg, France), probably Blois, France, enamel on copper with brass band, gilded metal hand, and modern crystal. Taft Museum of Art, 1932.64

Caspar Cameel (French, active from about 1625), watchmaker, Watch with the Judgment of Paris, about 1640, with early- to mid-17th-century movement (Strasbourg, France), probably Blois, France, enamel on copper with brass band, gilded metal hand, and modern crystal. Taft Museum of Art, 1932.64

Caspar Cameel (French, active from about 1625), watchmaker, Watch with the Judgment of Paris, about 1640, with early- to mid-17th-century movement (Strasbourg, France), probably Blois, France, enamel on copper with brass band, gilded metal hand, and modern crystal. Taft Museum of Art, 1932.64